Q San Francisco

January 2001

Pages 56-57

Hot & Spicy

In the town that I grew up in there were two Chinese restaurants. Both served what I’ve since come to regard as watered down Cantonese-American cuisine; sweet and sour shrimp, chicken with snowpeas, pressed duck, chow mein – you know the drill.

I remember in high school when a third restaurant opened serving Szechuan and Hunan food. All of the sudden there were hot peppers, ginger, garlic and onions. This was a brave new world for those of us who thought extreme heat was drinking the red sauce that came with a Taco Bell taco.

The first time I tried some, I instantly fell in love with spicy foods – and thus began a long and exciting journey of exploration into foods that have some zip. Bottles of hot sauce were consumed, and no pepper was left unturned; but somewhere along the line it became clear that this was all just about heat and pain – what was needed was balance.

The first time I tried some, I instantly fell in love with spicy foods – and thus began a long and exciting journey of exploration into foods that have some zip. Bottles of hot sauce were consumed, and no pepper was left unturned; but somewhere along the line it became clear that this was all just about heat and pain – what was needed was balance.

In the past few years I’ve returned to exploring the world of Chinese and other Asian cuisines. A few millennia of kitchen time suggested that there had to be something more to these foods than just a chance to sweat. Sure enough, there’s lots to eat, lots of spice, and, most importantly, lots of flavor!

The provinces of Szechuan (Sichuan) and Hunan are located in west-central China. They comprise an area that is at the core of the most ancient parts of Chinese culture. Hunan is a well-cultivated area that provides a huge range of vegetables for use in cooking. Szechuan is a mountainous region with a more limited selection of vegetable foodstuffs, but a larger selection of wild game.

Much of what is used in the cooking of these regions is medicinal in origin. The use of chilies is, historically, a way of inducing perspiration to stave off excess “dampness” in the body. In areas where humidity is high, this can help promote better health. In addition, chilies are a natural antiseptic.

What is most distinctive about these cuisines over other Chinese regional cooking is the emphasis on freshness and flavor over color and presentation. It is a more pragmatic, home-cooking style of food preparation. Dishes commonly open with a pungent, up-front “assault” on the palate that quickly subsides and opens up the taste buds to a wide range of flavors.

It is very common in the food of this region to make use of the traditional Chinese medicinal theory of tastes – sweet, sour, salty, pungent, and bitter – in combination in each meal. Potent, stimulating meals are common: the theory being that they are best suited for promoting active, energetic lives in response to a hot, humid climate.

One of the first dishes from this region I ever had, and still one of my favorites is the ubiquitous “Kung Pao Chicken”.

Kung Pao Chicken

1 pound boneless chicken breasts

2 tablespoons soy sauce

2 tablespoons rice wine

1 teaspoon sugar

2 teaspoons cornstarch

1 scallion, chopped

2 teaspoons chopped fresh ginger

Cut chicken in bite size pieces, mix with the other ingredients and set aside for half an hour.

5 fresh hot chilies

1/4 cup raw peanuts

1/4 cup peanut oil

Heat oil and fry the chilies until they turn dark brown. Remove and set aside. Add the peanuts to the oil and fry until golden brown. Remove and set aside.

3 scallions, sliced

6 cloves garlic, sliced

3/4 cup chicken stock

2 tablespoons soy sauce

1 tablespoon rice wine

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon sugar

2 teaspoons cornstarch

1 teaspoon red wine or brown vinegar

Pour off all but three tablespoons of the oil and stir-fry the chicken for 2 minutes. Add the scallions and garlic and continue to stir-fry for another minute. Add the chili peppers back in along with the chicken stock, soy sauce, rice wine, salt, sugar and cornstarch (mixed together to dissolve the solids). Cover and simmer until the chicken is tender and cooked through, 3-4 minutes. Add the vinegar and the peanuts, toss together and serve.

What Wine Do I Serve?

My current “fave” in the wine world to accompany spicy food is the Viognier grape. This white varietal originates in the northern Rhone valley in France where it is the constituent of such famous wines as Condrieu and Chateau-Grillet, and an aromatic addition to the red wines of Cote-Rotie. In recent years, it has become the darling of the California “Rhone Rangers”, and more and more, deliciously dry, aromatic and richly flavored wines are being turned out domestically.

Some producers I’m particularly fond of from the home front are Arrowood and Kunde from Sonoma, Alban from San Luis Obispo, and Rosenblum from Napa. In the Rhone world, keep an eye out for Gangloff, Andre Perret, and Pichon. If you want to try something truly esoteric, and in truth, a bit odd, give a shot at a bottle of Chateau-Grillet.

Q San Francisco magazine premiered in late 1995 as a ultra-slick, ultra-hip gay lifestyle magazine targeted primarily for the San Francisco community. It was launched by my friends Don Tuthill and Robert Adams, respectively the publisher and editor-in-chief, who had owned and run Genre magazine for several years prior. They asked me to come along as the food and wine geek, umm, editor, for this venture as well. In order to devote their time to Passport magazine, their newest venture, they ceased publication of QSF in early 2003.

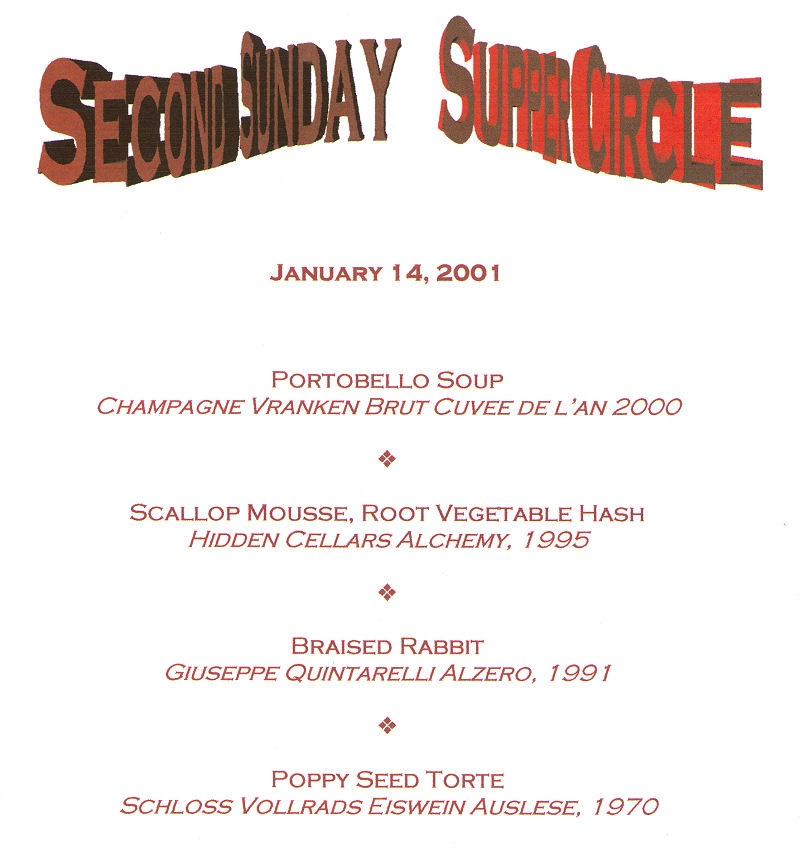

Although the whole Y2K thing was oriented around the change in the year from 1999 to 2000, because of some potential computer glitches (that didn’t happen, but the hype surrounding it all was impressive), the actual date of the change of the millennium was January 1, 2001, not 2000. We celebrated with an understated dinner.

Although the whole Y2K thing was oriented around the change in the year from 1999 to 2000, because of some potential computer glitches (that didn’t happen, but the hype surrounding it all was impressive), the actual date of the change of the millennium was January 1, 2001, not 2000. We celebrated with an understated dinner.