Made in Argentina

Buenos Aires for Visitors

Summer/Autumn 2009

Page 55

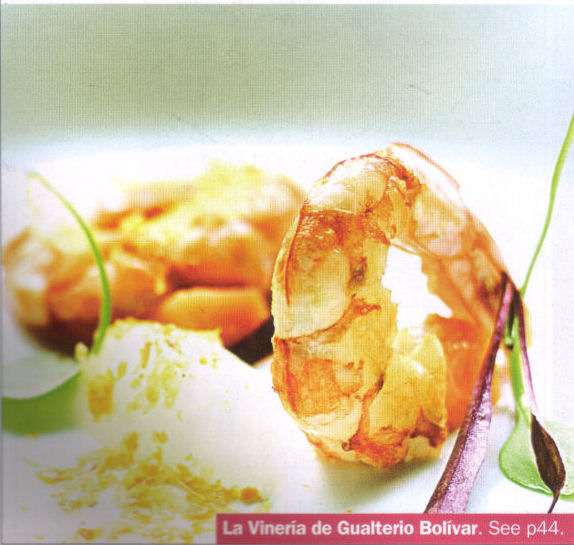

We salute the emergence of a new wave of chefs unafraid of mixing tradition with innovation.

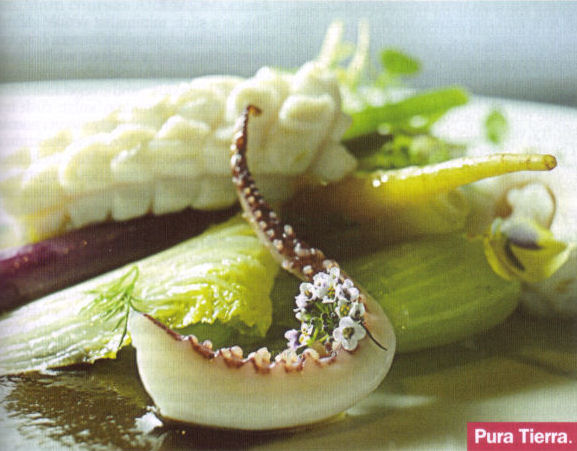

With a focus on new uses for local and regional ingredients, Martín Molteni, chef at Pura Tierra, is experimenting with feverish intensity to find the best ways to use those products that Argentinians have forgotten are part of their heritage – quinoa, amaranth, herbs, wild game and fish. In his view, ‘Argentina is a nation in search of a culinary identity… it is the responsibility of chefs to not just help someone get their certification but to develop their future, their palates and their curiosity.’

Chef Molteni takes classic regional dishes – primarily fish and game dishes, and others which utilzie these lost ingredients – carefully deconstructs them, and puts them back together as spectacularly presented plates that would not be out of place in a top dining establishment in any food capital of the world.

One of the things he focuses on is the lack of inspiration and drive among young chefs to get themselves out there and learn, experience and grow. His approach with both staff and customers is to guide them through tasting the purity of individual ingredients, each prepared in a variety of ways that show off, say, a tomato, at its best. a recent visit showcased them at their best: cured bondiola, one of Argentina’s favorite cold-cuts, alongside amazingly small cubes of fresh tomato; an intense tomato compote served beneath a locally made artesanal burrata cheese; and moments later a cut of ocean-fresh corvina atop roasted tomatoes. He is working to generate in others the same curiosity that he discovered in himself as he spent 16 years working in other chefs’ kitchens in Argentina, Australia and France.

For his part, chef Javier Urondo, of Urondo Bar in Parque Chacabuco, takes as his creative starting point what the average visitor or local might consider the ‘cuisine of Buenos Aires’ – tablas, milanesas, steak, french fries, and so on. His plates are easily recognizable as Argentinian. As he puts it, ‘I like to serve everyday dishes with something simple and different that makes them surprising.’ A perfect example would be a beautifully seared steak served with a spicy garlic puree and accompanied by a risotto flavored with his home-made horseradish mustard; or his signature copetín, a classic collection of vegetables and meat hors d’oeuvres that any Argentinian would recognize – until they bite in and experience the influence of exotic herbs and spices, a different technique applied to each one. He sees hope for the future of local cuisine, with new sources of fresh fruits and vegetables, meat, fish and dairy emerging – all things that Argentina excels at producing, but historically has exported rather than offered to its own citizens. However, as more locals travel, and more foreigners arrive, the interest and demand for ‘something more’ has arisen.

Some of this demand is being satisfied by ‘ethnic’ restaurants serving cuisine from Asia or other Latin American countries. Some is being addressed by the culinary vanguard, with modern techniques and presentations and a strong European or North American base. More recently, there’s been a quietly growing movement of ‘modern Argentinian’ cooking, with chefs like the two profiled above and others like Diego Félix at Casa Félix and Martín Baquero at Almanza, taking the lead. Local dining is already looking more interesting.

In mid-2006, I started writing for Time Out Buenos Aires. With changes in their way of conducting business, I decided to part company with them after my last article and set of reviews in mid-2009.

Buenos Aires – Though it was published last year, I just got around to reading through Daniel Leader’s Local Breads. I was particularly interested in this bread baking book because it focuses on sourdough breads from a number of traditional European cultures, and it’s a topic, good sourdough bread, that is, that comes up regularly in expat conversation here. A friend of mine recently went back to the U.S. to visit family and agreed to bring back a couple of different books that I’d wanted, so here was my opportunity. Daniel Leader is well-known for his award winning book Bread Alone that came out in the mid-90s – a solid introduction to the world of bread baking. This new book has gotten rave reviews, with only minimal criticism for at times being a bit technical and dense. I have to admit, I didn’t find it that way, but then, I’m kind of used to reading books of that sort.

Buenos Aires – Though it was published last year, I just got around to reading through Daniel Leader’s Local Breads. I was particularly interested in this bread baking book because it focuses on sourdough breads from a number of traditional European cultures, and it’s a topic, good sourdough bread, that is, that comes up regularly in expat conversation here. A friend of mine recently went back to the U.S. to visit family and agreed to bring back a couple of different books that I’d wanted, so here was my opportunity. Daniel Leader is well-known for his award winning book Bread Alone that came out in the mid-90s – a solid introduction to the world of bread baking. This new book has gotten rave reviews, with only minimal criticism for at times being a bit technical and dense. I have to admit, I didn’t find it that way, but then, I’m kind of used to reading books of that sort.