Banned in 2022 #2

Picking up with a few more of the books that were “banned” this year. Again, not banned in total, but a scattering of school boards voting to remove them from all or some (generally grade specific) school libraries. I went into a bit more detail about the whole movement this direction in the first post.

Gender Queer: A Memoir, by Maia Kobabe

Gender Queer: A Memoir, by Maia Kobabe

This book has come to be known as one of the most banned, or at least most requested to be banned books of late. The general claim of those who want it banned is that it’s pornographic. The general claim of those who don’t want it banned is that it’s a frank and much needed discussion of coming to grips with gender identity.

I’ll say, they’re both right.

This is a graphic novel, a comic book, if you will. It’s well drawn, it’s well written. It is, indeed, a very open autobiography of the author’s process of self-discovery in terms of “er” gender identity. The author chooses the pronoun set of e/im/er along the way. While I can’t personally identify with the particular identity struggle, I well remember how much I would have loved to have access to books that would have helped me with the struggle of identifying being gay, and what it was all about. Some of it was simple lack of existence back in the early 70s, but even of those books that did exist, I don’t think any were in our school libraries, and my recollection is that the few in our public library were near impossible to check out without blatant attention being paid. I’d read them at the library and reshelve them myself. On that basis, I side with the supporters.

On the other hand, what about the pornography claim? Is it just an attempt, as the author and friends say, to get rid of the book? I guess that comes down to how you define pornography – the old, “I can’t tell you what it is, but I know it when I see it”. It’s not pornographic in the sense of having blatant images of penises and vaginas going at it in one combination or another. On the other hand, it includes scenes of naked guys, gals, and other, angled in ways that genitalia aren’t visible… going at it. It includes frank descriptions of both masturbation and masturbation fantasies. It includes a description of giving a blowjob. It includes talking about smelling and tasting one’s own and one’s partners “juices”. And more; all accompanied by illustrations.

Now, is that pornography? It certainly, to me anyway, would qualify as “soft porn”. But at the same time, when I was growing up, we didn’t have the internet. We might here and there spend some time with a “nudie magazine”, but, certainly I’d never seen one that was gay themed. I’d venture that most high school students these days have long ago mastered finding hardcore porn on the web and the depictions in this book will probably barely register. At a younger age? I understand parental concern, especially as (I’m guessing) younger kids may well not have access to or have seen the more blatant stuff. Yet.

This one’s a tough call.

Lawn Boy, by Jonathan Evison

Lawn Boy, by Jonathan Evison

Honestly, I’m not quite sure what the controversy is over this book. The claims seem to be that it’s some sort of celebration and graphic illustration of pedophilia. The other side says it’s just an attempt to cancel the experience of a poor, biracial kid… “like the author”, as the tag “semi-autobiographical” gets appended time and again.

Let’s start with the last part of that. It’s not really autobiographical. The author himself says it’s not based on his life, but rather was inspired by one of his nephews who is biracial, though apparently neither poor nor being raised by a single mom. On the other side, Evison was raised by a single mom. From anything I’ve been able to find online, it doesn’t quite sound like it was the intense struggle. I mean, Evison grew up on Bainbridge Island, median family income over $160k, 90+% white. I’m not discounting that his family might have been one of the few hundred on the entire island who are at the low end of the income strata, but we’re not talking West Compton here. He talks about having gone through several jobs in his teen years, sort of drifting from one to the next. Sounds like half the teens I’ve ever met, regardless of income level.

But let’s set that all aside – I could be totally wrong about his life – I’m basing it on what I can find on the web. To the book!

Is it pedophilic? No. Just a plain no. I’ve read and reread the passages that get quoted, which indeed are about some sexual experimentation the protagonist has had. But it’s all kids or teens with other kids or teens. Actually, “all” is a stretch. It’s a return, several times, to a few experiences with one other kid that started when he was ten years old. And now he’s miffed that in their early 20s, the other kid, now also a young adult, married, with family, doesn’t want to acknowledge that they used to diddle each other. A lot of young boys “mess around”. There were no adults involved, and with all the rereading of the passages I’ve done, it would take a special kind of warped mind to make the jump that because it’s an adult writing the book, it’s really about his creepy obsession with young boys. He’s writing a coming of age novel. Of course it’s going to involve young boys and teens. Tempest in a teapot, as they say.

Here’s where I have issues with the book. It’s written in the first person, and this middle aged white guy writing it just doesn’t come across as a 20-something Mexican-American kid. Not even a little bit. Instead, it comes across to me like “I, author, am going to try to dumb down my speaking patterns to show you how a young, biracial person would talk. As much as I can, because, you know, I can’t quite dumb myself down that much.” My negative about the book is that it comes across as blatantly racist and condescending on the part of the author. After that, I couldn’t care less about a couple of ten year olds touching each other’s wee-wees. I’m actually surprised that it gets as much support from the woke world as it does – it was so noticeable to me that I’d have thought they’d have trashed the book for that.

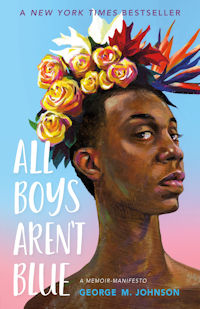

All Boys Aren’t Blue, by George M. Johnson

All Boys Aren’t Blue, by George M. Johnson

Okay… I’m going to be treading on thin ice here with this one. Pretty much everyone who criticizes this book, regardless of their criticisms, gets immediately and loudly labeled as racist and transphobic. The banning attempts seem mostly related to a trio of passages in the book that are graphically sexual – one a situation of the author being molested as a child by an older family member, the other two descriptions of their (Johnson identifies as non-binary and uses they/them/their pronouns) first consensual sexual experiences.

Let’s start with the outcry against the critics. It’s not automatically racist or transphobic to criticize a book simply because it was written by a person of color or a trans or non-binary person. It’s not “they’re being mean to me because of my identity”. Not everyone is a good writer, and being black, brown, or trans does not auto-endow anyone with literary ability. So let’s look at the book.

First, the sexual stuff. It’s there. It’s graphic. Again, as I noted above, it’s probably far less graphic than 99% of what teens can find on the internet, and watch videos of. But it is there. On the other hand, it’s a yawn, because… this is just a poorly written book. It’s a series of autobiographical essays, but rather than exuding any personality, emotion, or warmth, chapter after chapter comes across like a high school book report that was written the night before it was due. Even the graphic sex comes across like a reporter felt the need to include something in a WaPo article on sexual molestation or homosexual activity. Now, in an autobiographical book, it’s not unexpected that it’s written as if the author is the center of the universe. Better writers might not do that, but most do. It’s a natural tendency when talking about your own life.

But Johnson carries this to an extreme. Everything is all about them. As a small child, they and their brother get jumped while walking down an alleyway in a sketchy area of town. They, in retrospect, conclude that this was their first time being gay-bashed. They were five years old. The older kids, known local bullies, jumped them, beat them up, and took their lunch money. No one used a slur, no one tried anything sexual. Later in life, Johnson relates the trauma of coming to grips with their identify on finding out that the name they’ve been called for the first few years of life is actually their middle name, not their first name. This is, apparently, akin to the trauma of discovering one’s gender isn’t what one thought it was, albeit both names are boy’s names. The author, despite the trauma of being misnamed, regularly uses the “deadname” of a trans cousin, because “it’s funny”, and uses stereotypical slang and slurs against others. But when similar word choices are directed at themself (this is hard to use pronouns this way), it’s suddenly offensive and soul destroying. Johnson even claims to have invented an entire subculture of LGBT language, starting with the use of “Honey Chile”. Johnson was born in 1985. I have gay friends from the south who were using it, and other of his “inventions” in the 70s.

And more. The credit given to Nina Simone for the 1965 song “Strange Fruit”. The song was first performed by Billie Holiday in 1939, from a 1937 poem written by a Jewish poet, Lewis Allen, as a protest against lynching. The jumble of Abraham Lincoln quotes taken out of context and chronological order to make it seem like he was never anti-slavery, rather than that it was a slow development and change later in life. Even simple things like dates – a claim that the day of the 9/11 attack was his first day of his junior year of high school… really? A high school that doesn’t start classes until mid-September? And starts on a Tuesday? I’d venture they were at least a week or two into classes by then. I suppose I could be wrong about that, but I’m betting not. And of course, the attack deeply affected Johnson’s personal gender and racial identity.

I wish I could see the positives that supporters of the book see – the explorations of “young, black, queer identity” – and no doubt they’re interwoven into the book. But they’re so obscured by self-importance and bad writing that they’re lost. I wouldn’t ban this book based on a trio of graphic sexual encounters, but on the basis of being a book that should have been not just better written, but had a decent editor involved. I find myself trying to imagine any decent editor who would have let this one get past them. Unless they were afraid they’d be canceled as racist and transphobic for taking a blue pencil to it.