Cuisine & Vins

May 2008

cuisine insider tips

A walk on the gaucho side

Argentina offers one of the most delicious cooking in the world. Cocina de campo is a treasured secret that every tourist want to find out. [This was a copy editor’s addition, obviously not fluent in English.]

Trying to define what “country style” cooking is depends not only on what country you’re from, but on what part of that country as well. Whether it’s a farmer’s breakfast from the Midwest of the U.S. stacked with pancakes, hash browns, eggs, bacon, sausage, and ham, all at once and on the plate or an English ploughman’s lunch with cheddar, Branston pickle, bread, butter, boiled egg, apple, and a green salad – the one thing you can bet on is it will be filling, nourishing, and hearty. After all, country living tends to be hard work, and you need something to keep you going. Here in Argentina, as in many places, stews and casseroles are the order of the day, and they are plentiful.

In the stew category, a quartet make up the core of cocina de campo here. Locro starts with a base of dried white corn or hominy, with the addition, almost always, of potato, squash and sweet potato, which are often cooked until they’re literally fallen apart and become part of the liquid that surrounds the bits of diced meats and sausages. Depending on where its from it can range from mild to spicy, usually a simple matter of either green onions, chili flakes, or chili oil being added to or not; and from some regions, a bit of cheese is added atop and melted just enough to be able to stir it in. Carbonada can be, in some ways, similar to locro, though often a bit on the lighter side, and characterized in particular by the addition to the stewing mix of pieces of sun-dried peaches that give it its unique flavor; and using fresh corn rather than dried white corn, either loose kernels, or, more commonly, sliced rounds of corn on the cob. The next two are probably more widely known throughout the Americas, lenteja is a lentil stew, generally with bits of meat and sausage lurking within, and mondongo, a tripe stew flavored with tomatoes, onions, and herbs, and a generous addition of potatoes.

It would not be out of place to look at Argentine country casseroles and find them familiar – one of the most common, the pastel de papas is little different from a classic shepherd’s pie, generally made with diced steak beneath its browned crust of mashed potato. Variations do occur, and the potatoes may be replaced with squash or sweet potato, respectively called by most, cacerola de lomo con calabaza or con batata. One unique dish is the humita casserole, a baked dish of sweet corn, often spiced with what we might think of as sweet spices – cinnamon, nutmeg – and sometimes even sweetened with a bit of sugar – and topped with cheese before baking. It’s a simple dish, but completely delicious, and is also often found, tamale style, in small portions steamed in corn husk, or as a filling for empanadas.

While a trip out to the countryside and a day, or weekend, at an estancia, or ranch, is a great way to get to try some of these dishes, or even spending the time at Buenos Aires’ nearby “gaucho town” of San Antonio de Areco, an easy bus or car trip of less than two hours, and which you can do on your own or with a guide. But for the short-time visitor or someone who simply prefers not to venture out to the countryside, the city abounds with options for rustic, campo cooking. One favorite spot at which to sample many of these dishes is La Payuca, with two locations, at Santa Fé 2587 in Recoleta and Arenales 3443 in Palermo, serves up piping hot bowls of all four of the above stews and a few variations of the casseroles, in traditional clay dishes, and right out of a wood-fired oven. La Payuca’s locations are big, bustling places, that might at first strike one as a sort of touristy spot, but listen up and you’ll realize you’re surrounded by locals just looking for good country fare. They’ve also got a reasonably extensive wine list, and a good selection of wines by the glass to accompany your meal.

Another favorite, of both the local and tourist sets, is La Querencia, with three locations, Chenault 1912 in Las Cañitas, Paraguay 434 in Retiro, and, probably its most popular locale, at the corner of Junín and Juncal in Recoleta. The versions served up here are, perhaps, slightly less rustic in style, with just a touch of city-refinement, but filling and delicious just the same. Their wine program is limited, but a simple flask of house wine actually fits the bill perfectly with this sort of food. Your choices are by no means limited to these two spots, and country fare is very popular, especially in colder weather, with the local populace – as the temperature drops, signs appear in restaurant windows like mushrooms after a storm – “Locro hoy!”, “Hay Mondongo!” – they won’t be hard to find.

In October 2006, I started writing for this Spanish language magazine, covering their English language section for travellers. I wrote for them for about two years. The copy editor, apparently not fluent in English, used to put each paragraph in its own text box on a two column page, in what often seemed to be random order, making the thread of the column difficult to follow. I’ve restored the paragraphs to their original order.

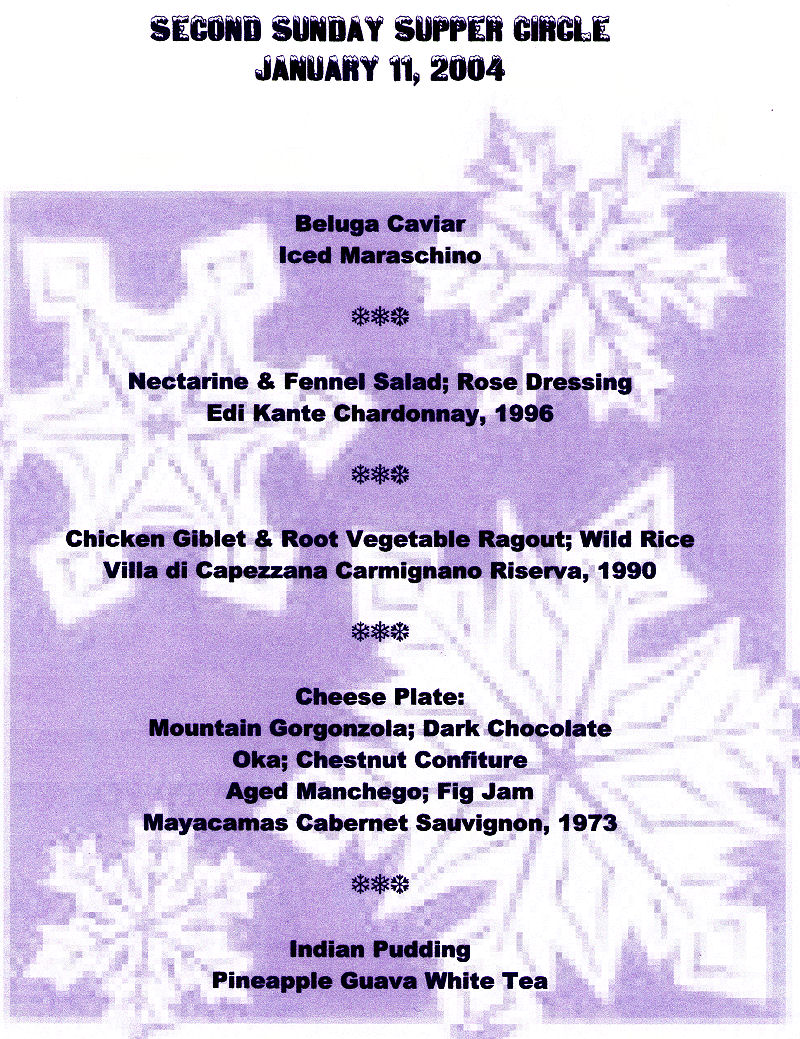

, where one of his characters is describing it as a far better match than caviar and champagne. The timing fits, the book was published in mid to late 2003, so I’d likely just read it, but I’ve just done a word search through my ebook version of the tome and not found it. There is a caviar eating scene in his book Cryptonomicon

, but no Maraschino mentioned. So I’m at a loss now to recall where I read the scene. Nonetheless, at the time, I decided to give it a try, and it’s actually quite true – it’s an amazing combination. Where whomever wrote it got the idea from, I have no idea, it’s not something that I’ve encountered anywhere else in gastronomic literature (or any other literature for that matter).