Cooking the Books #1

Like my new little series of “Bite Marks” on my food blog, SaltShaker, for mini-restaurant reviews, I’m trying to be a bit more organized, and I thought I’d start with doing much the same with book (and other media) reviews. Let them be gathered together and all that….

So I have this vague recollection that a few years ago someone told me about a new food novel about some Indian chef in France. It sounded kind of interesting, but I forgot completely about it. Then, of course, last month, everyone started going gaga over this new film about some Indian chef in France. It sounded kind of interesting, but I thought I’d read the book first. And there on the cover of The Hundred-Foot Journey is a quote from Anthony Bourdain claiming that it’s the bestest everest novel set in the cooking world that’s ever been published, or something to that effect. Novel, mind you, not best cooking or chef or food book. But that’s a pretty bold claim and a big gun name to get on the cover of your book. So I sat down to read it. And read it. And… pretty much, I couldn’t put it down.

I ended up reading through it over two evenings, before bed. I got completely caught up in the story, the writing is tight, well paced, and I thought the story developed beautifully, I found myself right there along with the protagonist, our erstwhile Indian chef in France. I loved it from cover to cover, be it the food and ingredient descriptions, particularly those relating to his Indian influences, and I could see exactly how his drive to succeed pushed him into this world without social connections – it’s what happens to many chefs who get singled minded in pursuit of their craft. At some point, it all comes crashing down, or, they find a balance.

And I started to think, there’s no way they could make this into a movie, no one but chefs would want to watch it, which means that one of two things has happened – either they’ve made a really arty film that will become a cult hit with people who are really into food – foodies, if you will, or, they’ve torn out the soul of the book and replaced it with some Hollywood feel-good storyline. The movie’s getting raves all over the place, take a guess….

[spoiler alert if you keep reading]

I just knew it, I never should have gone to see the movie (which, inexplicably, here is called Un viaje de diéz metros, or the Ten-Meter Journey, when it should be Thirty-Meters). I can’t say it was a heartless adaptation, because first, it wasn’t heartless, it was all about heart, it was all about romance – two parallel romance stories that never occur in the book, in fact, one of the romance lines involves two people who in the book are dead, part of what drives our young chef to become what he becomes – it was, however, soul-less. Second, it’s not an adaptation. That assumes that there is some relation to the original story, one that involved racism (in the book) rather than politics (in the movie) – oh so blatantly dropped out of the early scenes, in fact, the family name is changed from a Muslim one to a Hindi one (to be more specific, a Kshatriya clan name), just to bypass that whole arena (a bit of racism comes in later on, but that’s not until the family is in Europe). All the intense, graphic scenes of dealing with ingredients (like nearly a chapter spent on the hunting and butchering of a wild boar), are sanitized into an idyllic bicycle ride through the woods looking for mushrooms and the occasional fishing line cast into the river.

I could even forgive the romantic storylines and whitewashing the grittiness (whatever for? watching someone butcher a pig is far less gruesome than watching, say, an episode of Bones) that make the movie a box office draw if it wasn’t for the most egregious offense, one that amounts to food racism (and I’m a bit surprised, given some of the people who are behind the movie) – in the book, it’s our Indian chef in France’s refined, elegant, modern Indian food that shocks, surprises, delights, and opens doors, and the French food comes in later; in the movie, despite his evident passion, he’s shown cooking homestyle and street Indian food, and it isn’t until he embraces the French classics (and later molecular gastronomy, which never happens in the book) that anyone pays a moment’s attention. Indian food, it’s made clear, is something that Indian people eat, not those with any taste. At most, we can allow a few spices to be added to the “real” haute cuisine in order to make it a bit “exotic”, but no more. (Actually, there’s a whole second racist overtone – the family goes from in the book being well-off, well-dressed, albeit outsiders from India, to being relatively poor, grubby immigrants, and the family restaurant is ignored by the townspeople until the family starts dressing up in Bollywood costuming. Oh, Oprah, were you paying any attention? Or do you think the only people hurt by stereotypes are black?)

Now, how would I have felt if I hadn’t read the book first? Obviously, I can’t really know. Would I have picked up on the whole shift of cuisines? Probably not, but that’s also because he wasn’t shown making the elegant, modern style Indian food, he didn’t start going for elegance, presentation, refinement, until after starting to learn about French food. Had the movie followed the book, it might have been more evident. I wouldn’t have known about the dropped racism in India storyline. I wouldn’t have known there were no romances developing. I wouldn’t have known it was missing the deep diving into the guts of animals that was so graphically portrayed in the book. So my guess is, it would have come across as a reasonably well acted and directed story about love and a passion for food, albeit a bit schlocky. Read the book, save your movie dollars for when it shows up one day on WE tv.

Now, a bit less in-depth, just short thought on another book finished this week:

Awhile back someone recommended this book to me, I don’t recall who. Japanese Farm Food, by Nancy Singleton Hachisu and Kenji Miura, is a beautiful look at a type of Japanese cuisine and an approach to preparing it that most of us in the West probably will never experience. As such it’s a great journey, well illustrated and with easy to follow, step-by-step instructions. The flipside is that many if not most of us may simply not live somewhere with access to the ingredients necessary to make these dishes properly, and if there’s any fault in the book it’s the lack of suggestions for substitutions on ingredients, equipment and method. While I can appreciate the commitment to the integrity of the dishes and their tradition, it leaves much of the book as something interesting to read and dream about.

The current darling of the die-hard foodie set is Sandor Ellix Katz and his books on fermentation. This one came to my attention first, if I recall correctly through Aki and Alex over at

The current darling of the die-hard foodie set is Sandor Ellix Katz and his books on fermentation. This one came to my attention first, if I recall correctly through Aki and Alex over at

I truly don’t remember how this one came to my attention. I’m sure it was in some article I was reading about the history of American cooking that probably mentioned it, and I found this

I truly don’t remember how this one came to my attention. I’m sure it was in some article I was reading about the history of American cooking that probably mentioned it, and I found this

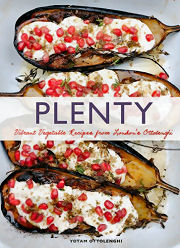

For those of you who like your vegetables, if you haven’t discovered London’s star chef Yotam Ottolenghi’s recipes floating around the ‘net, it’s about time you do. For awhile, from December of 2008 on, he wrote a column for The Guardian, called “

For those of you who like your vegetables, if you haven’t discovered London’s star chef Yotam Ottolenghi’s recipes floating around the ‘net, it’s about time you do. For awhile, from December of 2008 on, he wrote a column for The Guardian, called “

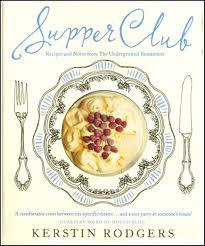

So Ted Allen has a cookbook too now, damnit. Oh, and so does Kerstin Rodgers. Better known to the world at large as Ms Marmite Lover through both her blog,

So Ted Allen has a cookbook too now, damnit. Oh, and so does Kerstin Rodgers. Better known to the world at large as Ms Marmite Lover through both her blog,